Nervous System: The IMpact of Trauma from a Clinical Perspective

Much of what trauma embodies is rooted in our nervous system’s response to and adaptation to the events occurring in our environment. Our nervous system is designed to help us survive and thrive in a world filled with both danger and wonder.

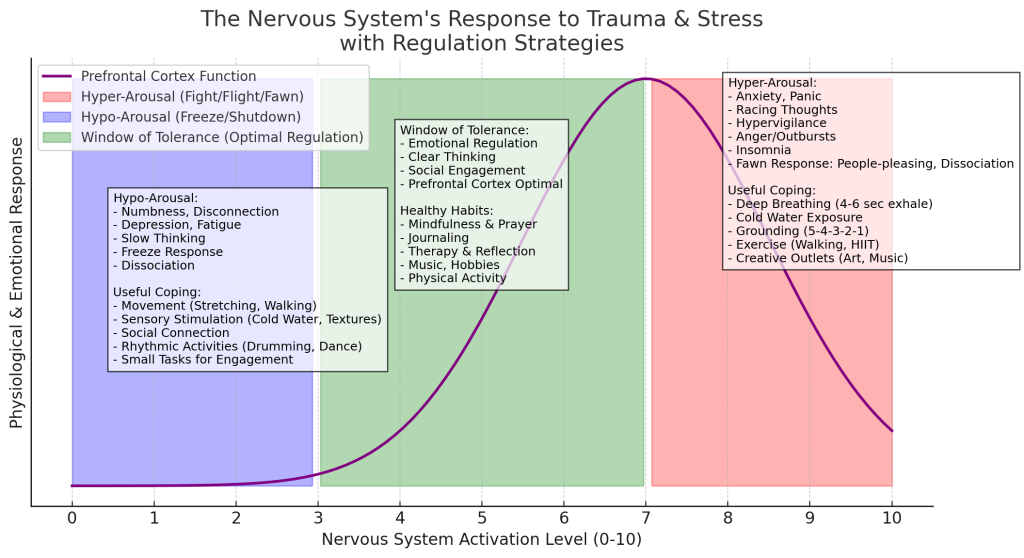

Below is a visual to help illustrate the workings of the Nervous System and its connection to trauma.

As you can see, the purple line indicates the function of the pre-frontal cortex (PFC). The PFC is the area of the brain responsible for making important decisions, inhibiting impulses, regulating our emotions, rationalizing, and more. Note that the functioning of the PFC is low on both ends of the spectrum.

When our nervous system is dysregulated, either through hyper- or hypo-arousal, our ability to think and behave rationally is significantly diminished12.

Hyperarousal

A state of hyperarousal (depicted in red) is defined by high nervous system activation (level 7-10), triggered by the body’s release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. This is the Sympathetic Nervous System. An individual in a state of hyperarousal will experience heightened anxiety, anger, tunnel vision, racing thoughts or rumination, difficulty sleeping, and more. This state is often referred to as the “fight or flight” response but can also manifest as the “fawn” response.

The Fawn response is a response of high dysregulation while the individual overworks to diplomatically decrease the threat occurring. Often this looks like bending over backwards to give an abuser what he/or she wants.

HYPO-AROUSAL

Hypo-arousal (depicted in blue), is quite the opposite. This is the Parasympathetic Nervous System. The individual in a state of hypo-arousal will experience numbness, dissociation, depression, fatigue, brain fog, and more. This often looks like the individual shutting down (oftentimes even in mid-conversation). A state of hypo-arousal can often occur as a response to a prolonged state of hyper-arousal or “sympathetic dominance”.

Window of Tolerance

The Window of Tolerance refers to our baseline of optimal functioning. This is typically how we feel when things are generally going well—after waking up from a good night’s sleep, enjoying a healthy breakfast, and sipping a warm cup of coffee. We feel prepared and capable of tackling the day’s challenges within the Window of Tolerance. Within this window, we are at our wisest, most loving, and most resilient.

The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System

You must understand that the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) operates without conscious control. It is regulated by the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that maintains homeostasis. Sensory data is gathered from the five senses, or the peripheral nervous system, and processed by the hypothalamus to determine which stress hormones to release into the nervous system through the endocrine system.3 The ANS is a necessary function of the body to keep us healthy and safe.

The Body’s Automatic Response to Danger

An example of this process occurs when my brain senses danger through my sense of sight (e.g., seeing a bear). I do not have to explain to my body the risks of a bear; my brain will automatically make a judgment call that the bear is dangerous and will utilize a stress hormone cocktail (adrenaline, cortisol, etc.) to activate my fight/flight response to energize me to get away. It is good for my body to experience fight or flight or even fawn when it works to help me survive.

The Impact of Trauma on the Nervous System

When we go through intense distressing events or endure prolonged periods of chronic distress, our nervous system becomes dysregulated. Our brains learn to adapt to their environment by overgeneralizing threats. For example, if my primary caregiver is unsafe, then people, in general, are perceived as unsafe. As a result, I must never let my guard down; I am always in fight-or-flight mode. Since our bodies cannot sustain perpetual fight or flight (i.e., “what goes up must come down”), when we are in prolonged “sympathetic dominance,” our bodies will eventually “slap back” to the other end of the spectrum. We may feel exhausted, depressed, isolated, and even suicidal.

Regulating Your Nervous System

Paying attention to your Nervous System Activation Level (0-10) can help you determine what actions to take to regulate it. We can actively regulate our nervous system through what are known as coping skills. If my activation level is low (0-3), I might go for a walk, listen to music, take a warm shower, or spend some time with a trusted loved one or pet. If I am highly activated (7-10), I might step away from what is causing the distress and practice some breathing, grounding, or relaxation exercises. Coping skills are not necessarily one-size-fits-all; the skills to use should be determined on an individual basis.

Understanding Your Story and Nervous System Responses

Once we have a solid grasp of how this system operates, we will have a useful framework for understanding the effects of our traumatic past on our nervous system. Reflecting on our experiences, we can identify when our nervous system activated in fight-or-flight mode, or we may have had to shut down, freeze, or dissociate to survive. When we understand this along with our life’s narrative, the challenges we face and the symptoms we experience become more manageable.

- Grossman, D., & Christensen, L. W. (2008). On combat: The psychology and physiology of deadly conflict in war and in peace (3rd ed.). Warrior Science Publications. ↩︎

- Thompson, C. (2010). Anatomy of the soul: Surprising connections between neuroscience and spiritual practices that can transform your life and relationships. Tyndale Momentum. ↩︎

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Hypothalamus: What it is, function & disorders. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22566-hypothalamus

↩︎